F&M Stories

Future Student Researchers Will Look Back Billions of Years

It sounds like a plot from a science-fiction film like "Interstellar," but in a few months, NASA will launch a telescope an estimated 1 million miles from Earth. It will allow researchers to peer back in time to just a few hundred million years after the Big Bang.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), the Hubble Space Telescope's successor, will carry among its many science projects one associated with Franklin & Marshall College. The data that it produces will engage F&M's future students in interstellar research.

"Our project is focused on detecting this light from really, really distant galaxies; the light has been traveling for about 12 billion years to reach us so we're looking almost 90 percent back to the Big Bang," Assistant Professor of Physics Ryan Trainor said.

For more information on how the $10 billion telescope looks back in time, read here.

The light Trainor speaks of is infrared, useful in detecting heat from relatively cool things in galaxies, and galaxies are what he studies. Trainor said that because of the expansion of space, the light thrown from galaxies in the early universe comes toward earth transforming into infrared light.

"It gets stretched from the visible part of the spectrum into the infrared part of the spectrum so we need infrared-sensitive telescopes to measure it," he said.

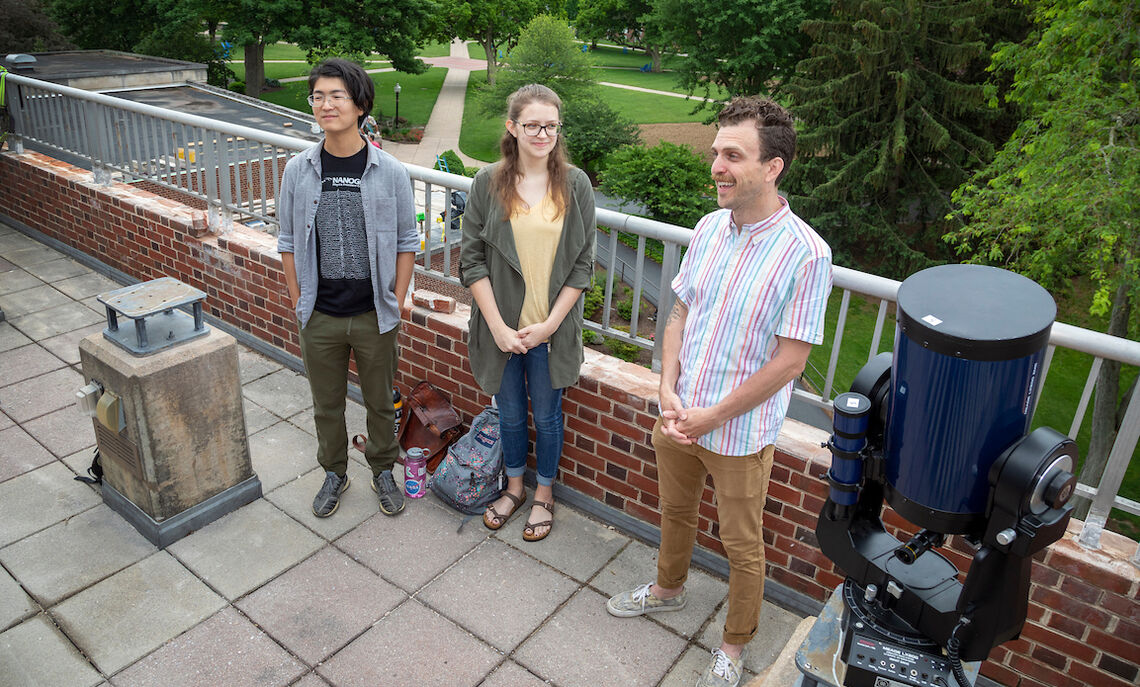

This summer, F&M rising seniors Becca McClain and Issac Lin are again assisting Trainor with his research. The students are performing data analysis on galactic activities from other telescopes and preparing for the JWST data that future F&M students will research.

"My project with Professor Trainor exposed me to real scientific research and provided me with a comfortable environment to practice scientific writing, reading academic papers, and giving research talks, all of which are very valuable skills in graduate school," McClain said.

As astrophysics majors, McClain and Lin said their research with Trainor inspired them to seek graduate degrees in the field.

"This project in particular has evolved into a source of stability in the 18-month-long marathon that we all unwillingly partook in, and it will metamorphose into a solid foundation for exciting new projects involving the JWST and an academic career," Lin said.

NASA is tentatively scheduled to send the JWST into the stars Oct. 31. It will take about a year to reach its destination, position in place, and begin transmitting back data for analysis.

"It's going to be several times the distance away from the moon, whereas the Hubble Space Telescope is a few hundred miles away, kind of zipping around what we call low-earth orbit," Trainor said.

The JWST's distant station in space should ensure its optimum effectiveness by avoiding the light pollution emitted from Earth.

"This whole telescope is designed to be really sensitive to infrared light, light that has longer wavelengths than our eyes can see," Trainor said. "It's the kind of light that detects anything at room temperature so you, me, the surface of the Earth itself are glowing all the time in this infrared light. It's similar to the light night-vision goggles can receive."

Larger than Hubble, which has a primary mirror at 2.5 meters in diameter, JWST's primary mirror is 6.8 meters in diameter, "the size of a classroom," he said. "Because the Earth itself is constantly glowing with this kind of infrared light, we have to put the telescope far away from Earth in order to measure the light from the galaxies."

JWST's instruments are specially designed to measure the formation of stars, planets and galaxies with extreme precision for the research Trainor and other scientists will require for their work.

"Basically, by precise measurements of light patterns, we make really precise measurements of all the physical properties of the gas in these galaxies," he said. "We're interested in understanding the process of galaxy formation."

"The biggest goals specific to this proposal are understanding when various elements in the periodic table were created over the history of the universe, and understanding the interactions of stars and gas in galaxies," Trainor said. "These are both questions that my students and I focus on in our research."

Technologically, JWST is a "vastly different instrument" than the more than 31-year-old Hubble, with a much shorter operational expectancy of at least five and perhaps even 10 years of active service before it depletes the fuel that it needs to keep operating.

"Unlike Hubble, JWST will not be able to be serviced or upgraded because it's going to be located much farther from Earth and so won't be accessible," Trainor said.

Trainor and his students are part of a team led by astrophysicist researcher Allison Strom of Princeton University. Their project will be among the first to use the telescope in late 2022 or early 2023. Other collaborative researchers are from the Carnegie Observatories, the California Institute of Technology, NASA's Space Telescope Science Institute, and Leiden University in the Netherlands.

"My students and I will likely lead the analysis of the faintest, youngest, and smallest galaxies included in the proposal," Trainor said. "F&M students will hopefully be among the first people to work with data from this upcoming cutting-edge facility."

Telescope's Name Controversial

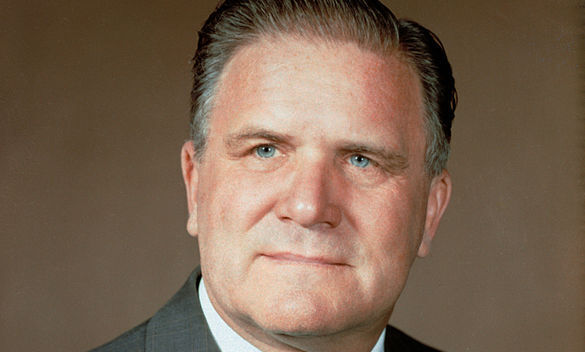

James Webb, the NASA administrator for whom the space telescope is named, was in part responsible for federal policies in the 1950s that resulted in purging LGBT individuals from the government workforce.

A March 2021 Scientific American article, "The James Webb Space Telescope Needs to be Renamed," details Webb's role in determining and carrying out the policy. NASA officials are apparently consulting historians to determine a course of action.

To Ryan Trainor, who has signed a petition that calls for renaming the telescope, Webb's action was unfair and not in the spirit of scientific discovery.

"My students and I are creating new knowledge about our universe, but we are also working to understand how science is embedded in the social and political questions that shape our experiences here on Earth," he said. "This is part of how we do science at a liberal arts college."

Related Articles

January 22, 2026

AI Research Bridges Environment and Economic Studies

How do you prove the economic value of clean water? Under the guidance of Professor Patrick Fleming, two students leveraged a unique combination of field research and AI to gauge Chesapeake Bay Watershed quality.

January 12, 2026

Behind the Scenes: Student-Coded Robots in Action

A group of international students spent the final weeks of the fall semester programming a robot to lead visiting students and families through a playful quiz about the College.

December 16, 2025

Research Club Kickstarts Students’ Science Careers

At Franklin & Marshall, a distinctive opportunity for hands-on learning gives students the chance to participate in collaborative research as early as their second week on campus. The Nanobots Research Club meets weekly and aims to help students interested in STEM research connect with each other in a casual, drop-in setting, while learning to use computational chemistry tools