F&M Stories

Your Brain: The Great Connector

Aristotle once said, "The whole is greater than the sum of its parts." As he shared his groundbreaking research in neuroscience, a Franklin & Marshall College professor pointed out that brain function closely follows that axiom.

"Any cognitive function takes many parts of the brain, and any part of the brain can be involved in many different cognitive functions," Michael Anderson told a well-attended Dec. 10 Common Hour, F&M's weekly community discussion.

"Thinking with your brain is also thinking with your hands," said the associate professor of psychology and this year's Bradley R. Dewey Award for Outstanding Scholarship recipient. He is author of the widely acclaimed book, "After Phrenology: Neural Reuse and the Interactive Brain."

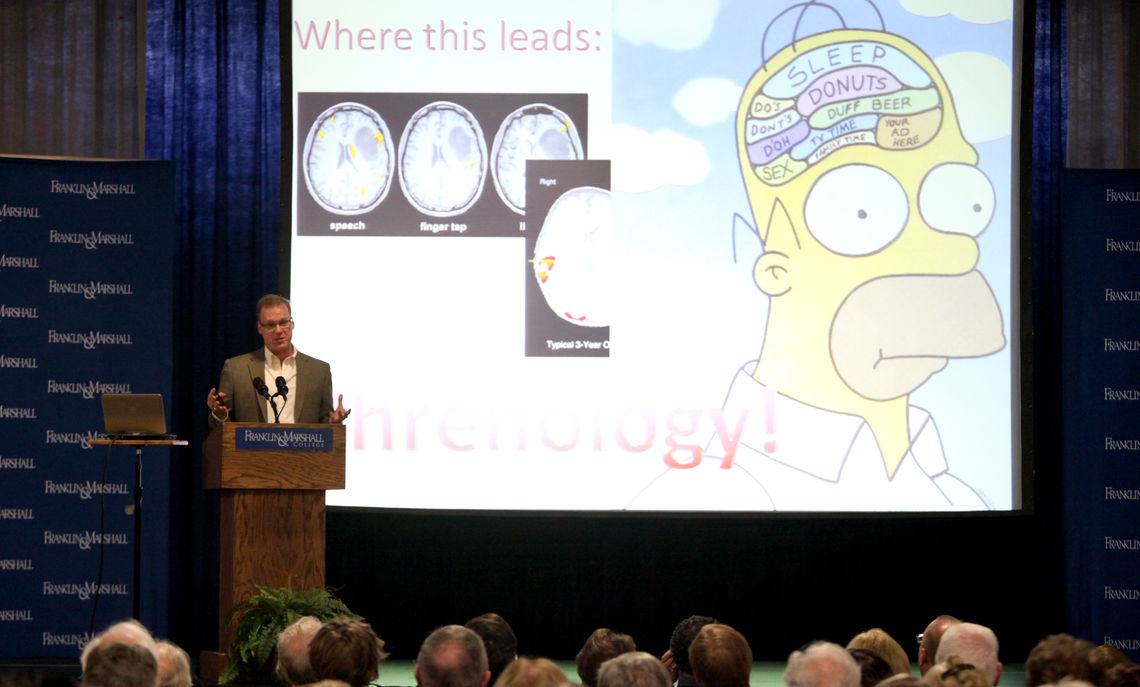

In his talk, "The Blue Collar Brain: How The Mind Really Works," Anderson said the brain is not, as scientists previously believed, a collection of specialized areas, each responsible for a particular task. Instead, it is composed of segments that multitask by connecting with other areas of the brain to perform functions.

"It's really about how the parts of the brain cooperate," he said, explaining that a section of your brain that is aware of your fingers also solves mathematical problems.

Anderson said the brain operates in this interactive way through neural reuse— parts working in tandem to support a variety of behaviors and cognitive skills— and through embodied cognition, which is the basic physical capacity for moving around in the world and manipulating objects that are crucial to thinking, including abstract thinking such as mathematics.

"Different parts of the brain are all quite diverse, but they are different from one another so you don't get function specialization," Anderson said. "They are capable of different things, and because they are capable of different things, they do different things."

He punctuated his points with charts and graphs, as well as images of the brain. "The neuroscientist union requires you to show pictures of the brain when you give talks on the brain," he lightheartedly told the audience.

At one point, he showed an image of the brain, divided in sections, and said each section is responsible for a different range of tasks.

"Each part of the brain has this characteristic profile," Anderson said. "We call them 'functional fingerprints.' These functional fingerprints differ from place to place, but they all are fairly complex and tell us something about what that part of the brain can do."

Seniors Tessa Grebey, an animal behavior major, and Sophia Blum, a neuroscience major who has Anderson as her academic adviser, were intrigued by the idea that all parts of the brain are connected.

"I think we're learning more and more that we're using our whole brain and not just parts of it," Blum said.

Sophomore Lauren Matt, who is considering a major in business, organizations and society, was most interested in the idea of the interactive brain.

"The idea that all parts of the brain are connected and not relying on a single part to function is thought provoking," Matt said.

Anderson has authored more than 100 scholarly and scientific works exploring psychology, neuroscience, computer science and the philosophy of cognitive science. He earned a doctorate at Yale University, and was a fellow at Stanford University's Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences in 2012-13.

Related Articles

February 20, 2026

Work on the Wild Side with Lillian Basom '08, F&M Vivarium Director

Lillian Basom ’08 loved Franklin & Marshall’s vivarium so much that she never left. In fact, she has been the director of operations since 2011. The research facility houses a variety of rodents, reptiles, birds, fish, invertebrates and capuchin monkeys.

February 16, 2026

A Q&A with Historian Manisha Sinha, F&M Mueller Fellow

Historian Manisha Sinha, this year’s F&M Mueller Fellow, will lead a Feb. 26 discussion centered on focus on her latest book, “The Rise and Fall of the Second American Republic: Reconstruction, 1860-1920.”

January 12, 2026

Behind the Scenes: Student-Coded Robots in Action

A group of international students spent the final weeks of the fall semester programming a robot to lead visiting students and families through a playful quiz about the College.