F&M Stories

F&M Biologists Contribute to Award-Winning Documentary

The film opens with a blue sky, viewed from under an alpine lake’s waters, and a soft-spoken narrator who sounds blue as she says, “Blue falls from the sky. It really does. It falls as light.”

The voice belongs to Leanne Allison, an award-winning Canadian documentary filmmaker, who is talking about the astonishing blue of glacially fed mountain lakes.

“A ray of sunlight contains every color of the rainbow. Light falls into clear water and from that moment water molecules begin to absorb it,” Allison adds. “Red light. Orange light. Yellow light. Green light. Every color is absorbed. Every color but one.”

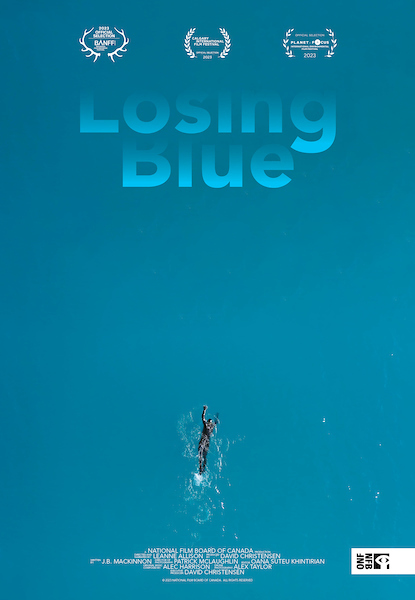

“Losing Blue,” a National Film Board of Canada production, is a collaborative effort between Allison, her writer James MacKinnon and two Franklin & Marshall College biologists, Professors Janet Fischer and Mark Olson, a wife-and-husband scientific team.

For nearly two decades, Fischer and Olson have brought F&M students to research the ecology of the lakes that are nestled beneath the snowy mountain peaks of Yoho and Banff National Parks in the Canadian Rockies.

Over the years, as the glaciers melt because of climate change, Fischer and Olson have detected subtle changes to the waters.

They decided to share this science through film. They approached Allison, whose documentaries include a radio-collared grizzly’s point of view and an epic journey following a caribou herd across the Arctic, and used some of their National Science Foundation (NSF) grant to start production.

“They had two stipulations: They didn’t want to be in it and they didn’t just want a conventional show-and-tell kind of science video,” says Allison.

The 15-minute film, screened at festivals in North America, won “Best Canadian Short” at the 2023 Planet in Focus Film Festival in Toronto. The online release is Jan. 31, 2024, by Living Lakes Canada; the U.S. premiere, in person and online, is Feb. 15-19 at the Wild & Scenic Film Festival in Nevada City.

“I think this project is an example of F&M’s commitment to the liberal arts and interdisciplinary work,” says Fischer, who along with Olson were science advisers on the film.

Fischer, Olson and Allison discuss the making of the film in this Q&A:

Q: What was it about the lakes that drew your research interest?

Olson: It started as a purely scientific interest. Janet and I were researching effects of ultraviolet radiation on aquatic ecosystems and we viewed mountain lakes as ideal study systems because they are highly transparent and at high elevation. We quickly found out that the lakes are highly variable in their color and their transparency, from one lake to the next.

Q: Is every lake crystal clear?

Olson: Many lakes are, but there are also many that are not. This variation reflects characteristics of lake catchments. In particular, transparency and color are affected by the presence and size of glaciers that feed mountain lakes. Glacial melt brings in finely ground rock flour, which reduces transparency and also absorbs and scatters light to make the blues and the turquoise. Our current research focuses on the implications of increasing transparency due to glacier loss.

Q: So, you followed your research and that is how you reached this point?

Olson: Yes. The lakes are an hour-to-two-hour hike—we carry all of our gear in; we unpack everything, take samples; and come back out. We run into people on the trail and we have these big packs with paddles sticking out of them so questions come up. One of the questions we always get is, 'Do you have a boat in your pack? ' But the question we get the most is about that unique [blue] color, 'Why are they that color?'

Fischer: They’ll also say, 'You know, I was here last month and it looked totally different.' Or 'My family comes and does this hike once a year and the lakes are different every year.' We feel like our research and our understanding of the lakes can help answer their questions. They’re naturally curious, which is really telling.

Q: So, the experience along the trail, of people asking about the lakes, prompted the idea of this movie?

Olson: Our funding agency, the National Science Foundation, requires a broader impact—What is the benefit of this research beyond publishing papers and training students? Early on, Janet said, 'We have this connection with people on the trail.' We need to do that with a larger group, and that’s where the movie came from. In fact, in the NSF proposal, Janet had the tentative title of 'Losing Blue' and the idea that the way to connect with people is through this movie.

Fischer: Right away, we reached out to Leanne about a possible movie, and thankfully, she was interested. We used a small amount of money in our NSF grant to contract with Leanne, who collected some preliminary footage. She took that footage and pitched the project to the National Film Board (NFB) of Canada. NFB produced the film, and also handles the distribution and promotion.

Q: How did your involvement as science advisers work in the film’s production?

Fischer: Early on, Leanne and screenwriter James MacKinnon joined us in the field. They received a crash course in alpine lake limnology and lake optics as they brainstormed ideas for the movie. James ran the script by us and many other mountain researchers, Leanne engaged us at every stage of filming —she shared raw footage with us and sought our input on the rough cuts, an early stage of the film production. We may have learned more about documentary filmmaking than they did about lakes.

During initial filming and researching, Allison, MacKinnon, Fischer and Olson would paddle together in packrafts.

Allison: Janet’s hunkering over her laptop and Mark is sending down sensors and I had my camera in hand and I started shooting down on the blue surface of the water—the blueness of that abstract shot was so mesmerizing.

The filmmaker lives near Banff and grew up visiting the lakes.

Allison: When Janet and Mark approached me with this idea, I hadn’t thought. ‘We’re going to lose the blue.’ I should have known this, but I didn’t; I hadn’t really thought of it. I think that’s part of what’s so compelling about this. There are 5 million visitors a year who come here who also don’t know this is happening.

As researchers, Fischer and Olson are dispassionate about science, but are thrilled that this film uses an artistic approach to reveal the beauty of the lakes and their color.

Fischer: I often tell the story to my students that the very first time that we hiked over the little crest and looked down on Lake Oesa, my eyes filled with tears. I was there to do science, but I was moved by the beauty of it. I think, as scientists, we sometimes push that down, that emotion, that humanity, but these lakes have become like old friends that we can’t wait to see each year. We love these systems and are grateful to Leanne for making a film that will inspire others to care about their future.

Related Articles

December 8, 2025

A Diplomat’s Deep Dive into Marine Biology

Learning by doing is part of our DNA as Diplomats. Jaeyun An ’26 dove headfirst into this philosophy, spending a semester in the turquoise waters of Turks and Caicos researching the island’s diverse marine life. “This experience gave me the confirmation that this was what I wanted to do for the rest of my life,” he said.

November 13, 2025

Trailblazing Research Examines Cigarette Label Alternatives

Three F&M students helped conduct a groundbreaking pilot study in Lancaster this summer, assisting Professor Hollie Tripp with tobacco regulatory research. It's the first F&M instance of biospecimen collection from non-campus participants.

October 23, 2025

Get to Know F&M's New Faculty

This fall, five new professors joined the Franklin & Marshall faculty—a vibrant community of scholars who shape the College’s distinctive academic experience. Their research interests range from parasitology to documentary film, from diplomatic networks in the Middle East to algorithmic surveillance online. Read on to get to know these new members of our campus community and hear what they had to say about the F&M experience, life in Lancaster, and more.